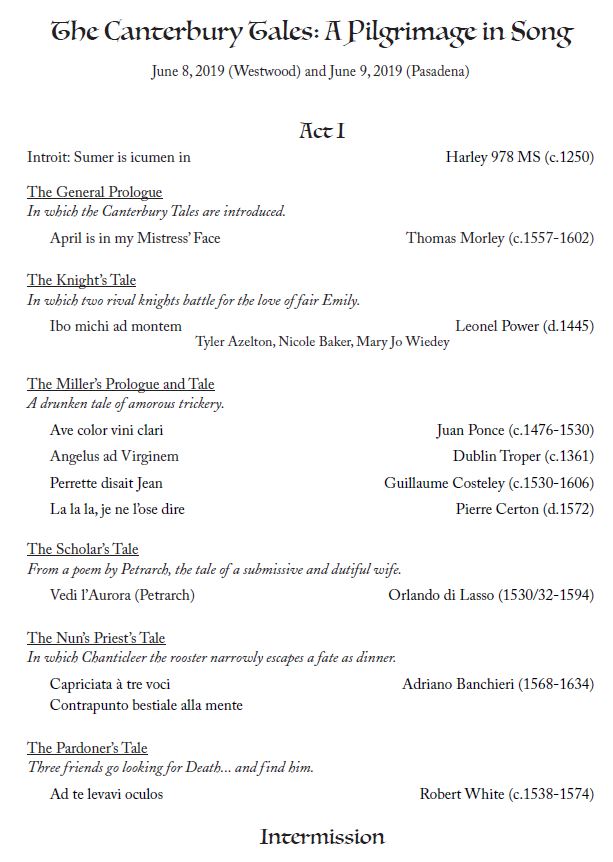

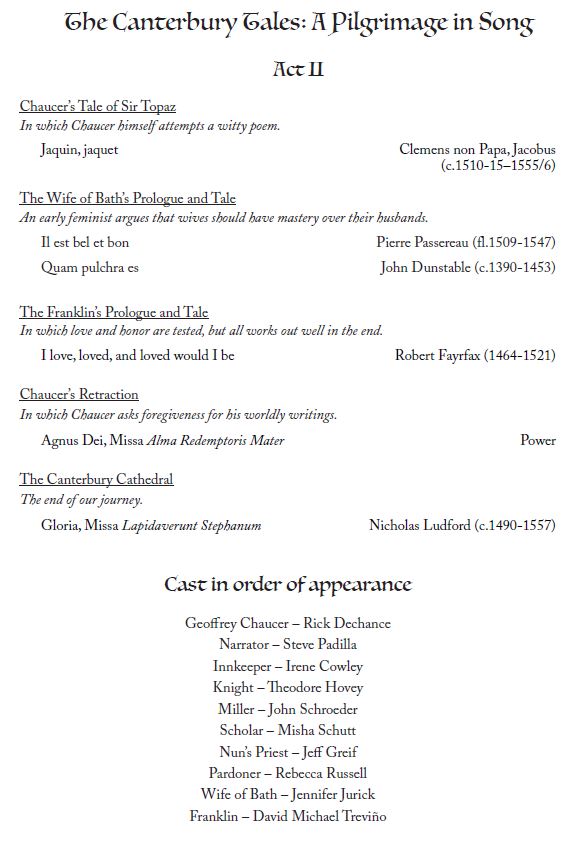

Jouyssance finished out our 2018-19 Season with a brand new narrative program, exploring the stories of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales via sacred and secular early choral works. This post presents the program, notes and selected highlights from these concerts.

An Early Music Father's Day!

On Saturday and Sunday, June 18 & 19, 2016, Jouyssance performed a concert dedicated to early music featuring father's and father figures. Here is the program and program notes from that event.

Jouyssance sings of all things fatherly at St. Bede's Episcopal Church on Saturday, June 18, 2016.

A Celebration of Father’s Day – Program Notes

by Nicole Baker, PhD

Welcome to Jouyssance’s Father’s Day celebration! You’ll hear about the God the Father, be he merciful, angry, our protector, or our leader. And when it comes to the father of the house, Jouyssance takes an admittedly archaic tack as it focuses on traditional concepts of men and family: you’ll meet hen-pecked husbands, rogues, drinkers, tobacco smokers, soldiers and hunters. Indeed, if we could have found a song about golf, it would have been here.

Highly prolific in his output, William Byrd produced works from viol consort music to Masses for private Catholic worship. His brief setting of a verse from Psalm 76, Terra tremuit, is often heard on Easter Sunday. Published in Byrd’s 1607 Gradualia, the work features some very obvious text-painting as the voices sing “and the earth trembled.”

The most successful Jewish composer of the late Renaissance, Salomone Rossi of Mantua was primarily a madrigalist, and he pioneered the important instrumental genre of the early Baroque, the trio sonata. Today, his best known works are his Jewish liturgical “motets.” His setting of an abridged version of the Kedusha (Keter) responses is surprisingly varied in its textures. The opening word Keter means crown, and it appears in ornate melismas in all voices. Eventually, Rossi settles into his usual homophonic texture, which is more in keeping with the early Baroque style favored in Mantua.

The anonymous Tappster, dryngker, amid all of its crassness, exhibits the sweet English sound, or contenance angloise that was a hallmark of the early to mid-15th century. Composed in the style of an English catch, it has parallel sixth chords typical for its time.

One of the finest composers of the late British Renaissance, Thomas Weelkes earned his degree at New College, Oxford, and spent much of his career at Chichester Cathedral as a singer, organist, conductor, composer, and teacher. Our first taste of Weelkes is the rowdy smoking song Come Sirrah Jack, ho, which sounds about as close to modern barbershop as late 16th century music can get. The song appears in the composer’s earthy and often topical 1608 publication, Ayeres or Phantasticke Spirites for Three Voices (his penchant for strong drink is evident in several selections). In Come Sirrah, the middle voice in effect operates in a different meter from the others, perhaps replicating the vertigo one might feel from too much tobacco.

Weelkes was also a prolific composer of service music for the Church of England, but much of it was lost. Fortunately, one of his surviving pieces is the poignant full anthem When David heard, which portrays David’s grief at losing his son Absalom. His tremendous talent as a madrigal composer helps convey the text through chromaticism and subtle word-painting.

Little is known about Pierre Certon: he worked at Notre Dame in Paris in 1529 and then moved to Saint Chapelle, where he served as master of the choristers. Certon played an important role in the development of the 16th century French chanson. The gossipy, rhythmic chanson La, la la, je ne l’ose dire exemplifies the mid-16th century Voix de ville — rustic songs centered on village life — and incorporates the dialogue style Certon favored.

One of the most diverse and prolific composers of all time, the Franco-Flemish composer Orlando di Lasso developed his international style by traveling throughout Europe as a youth in the service of the Gonzaga family. At age 24, with several posts already on his resume, Lassus gained a position at the Bavarian court in Munich, where he would remain for the rest of his life. As Hofkappellemeister, Lassus made Munich the most famous and lavish musical center in Europe. Published in 1565, the two-part motet Beati omnes qui timent Dominum shows an earlier, less chromatic side of Lasso. Giving each phrase of the psalm its due, Lasso flows effortlessly from one texture to another, indulging in occasional word painting along the way.

Later in the program we’ll present his delightful chanson, Quand mon mari. Published in 1564, the work shows Lasso’s ability to import Italian madrigalisms into French chansons. Full of irony and affect painting, he displays a mastery of textures that alternate between polyphony and homophony.

Kyrie Rex immense, Pater comes from the 12th century manuscript, the Codex Calixtinus of Santiago de Compostela. Musicologists believe that, despite its Spanish home, the manuscript originated in Aquitaine, the home of some of the earliest musically developed polyphony. The piece we present is a troped, or altered, version of a Kyrie.

The most famous Portuguese composer of his time, Duarte Lobo served as mestre de capela at Évora Cathedral and later in various posts in Lisbon. Lobo worked in a variety of styles, ranging from High Renaissance imitative counterpoint to early Baroque polychoral homophony. Published in 1621, Lobo’s Pater peccavi hearkens back to the style of Josquin, but incorporates characteristic Iberian chromaticism.

Possibly the last motet he composed, Josquin des Prez’s Pater noster/Ave Maria combines in one monumental work the two cardinal prayers of the Roman Catholic Church. Josquin left instructions and an endowment for it to be sung following his death at processions that went by his house in Condé-sur-Escaut. The moody, contemplative music departs from the more blatant imitative polyphony of his earlier days. Instead, the work includes numerous “hidden” canons that obscure his compositional method. Relatively austere and low in range, this motet features Josquin’s characteristic drive to cadences and an almost antiphonal nature.

A master of light madrigals, Thomas Vautor flourished in the early years of the 17th century, and most likely was based in Leicestershire, where he worked for George Villiers, the notorious Duke of Buckingham who may have had an amorous relationship with James I. All of his extant works are contained in a single volume, dedicated to Villiers. Witty and exquisitely crafted, Vautor’s Mother I will have a husband relies on a double-chorus texture, and no small amount of slang, to convey an argument between a precocious young girl and her mother.

Like many composers of chansons and madrigals, Pierre Passereau was widely praised in his time, but little is known about him. He is best known for lively, rhythmic works full of repeated notes and syllabic text settings that describe a situation or a story. Il est bel et bon appears in numerous editions, pointing to its popularity at the time (and now), and like many of Passereau’s chansons, deals with a rather unsophisticated subject in a witty, learned way. Listen for the onomatopoeic imitation of hens clucking.

Guillaume Dufay is arguably the greatest composer of the 15th century, and with England’s John Dunstable, helped launch the Renaissance. Often mistakenly linked to the Burgundian Court, he actually worked all over Europe, including Cambrai and Italy. Dufay composed his monumental isorhythmic motet Ecclesiae militantis for the coronation of Pope Eugenius IV on March 11, 1431. What makes this work particularly grand is the number of voices – normally there are three, but here we have five. The isorhythm appears in the slow moving lower two voices, or tenors, while the upper two voices sing different texts both praising Eugenius, and appealing to God the gentle Father for a return to peace in the Christian world. The upper two voices move fluidly and, progressive for its time, reflect the different moods of the text. All of the voices become increasingly complex in rhythmic design, leading smoothly into the brilliantly climactic final bars.

A onetime boy chorister at Canterbury and eventually a member of Chapel Royal, Edward Pearce is best known as the teacher of Thomas Ravenscroft. Few works of Pearce’s survive —

tonight’s charming A Hunting Song, with its nonsense lyrics and call-and-response interplay, is one of two secular vocal works extant.

The women of Jouyssance present the Franconian motet Psallat chorus/Eximie pater/Aptatur. Prior to the work of theorist and composer Franco of Cologne, rhythm in sacred music was limited to six patterns. Polytextual motets like this one are among the first to break free of the rhythmic modes and show some independence among the voices, thanks to a system of notation that serves as an ancestor to what we have today. The result is a delightful work involving two active upper voices and a slower moving, repetitive, lower voice.

The tune “L’homme armé” has served as the basis for some 40 settings of the Mass Ordinary from about 1450 to modern times, with Karl Jenkins’ the most recent. Johannes Ockeghem is generally considered the first “true” Franco-Flemish Renaissance composer. After stints in Antwerp and Dijon, Ockeghem moved to Paris, working for three different French kings. His music often involves complex metrical and canonic schemes that serve as the background for beautiful, consonant sonorities that served as the basis for the Renaissance sound. His Missa L’homme armé may not be as complex as other works of his, but the Gloria does present the tenor – the original chanson – in a different meter from the other voices.

Probably the greatest German composer of the late Renaissance, Hans Leo Hassler composed a wide variety of Masses, motets, canzonettas, Lieder, and keyboard music. Thanks to his study abroad, the Nuremburg native synthesized and brought back to Germany Italian compositional styles, particularly those found in Venice. It’s not known how much contact he had with the likes of Merulo, Gabrieli and Zarlino, but their work certainly influenced his, as can be heard in the brilliant, virtuosic, double-choir piece Cantemus Domino, published in 1615, which closes our program.